While I was browsing through a pile of Argentine Discomania revues from the early 1950s, I found this interesting interview with Carlos Di Sarli which I would like to share here. It was made during the rehearsals of the orchestra to prepare the first recordings at the brand new record label Music-Hall and it gives a very interesting insight on the scope and concept of this astonishingly progressive and well done recording project. It seems that in the beginning only around 5 records were planned with a total of 20 songs. And that the initial idea was to conquer new markets outside of Argentina, like Brazil, the USA and others. In that regard the use of vinyl makes perfectly sense as the format was about to spread from North to South America and it has by nature a better transportability either as flexible and unbreakable records or as tape copies. It also looks like as if the Di Sarli MH-project was not only meant to be distributed “for export” but also as an intercultural exchange where other local artists would share some tracks on the same albums with Carlos Di Sarli.

While I was browsing through a pile of Argentine Discomania revues from the early 1950s, I found this interesting interview with Carlos Di Sarli which I would like to share here. It was made during the rehearsals of the orchestra to prepare the first recordings at the brand new record label Music-Hall and it gives a very interesting insight on the scope and concept of this astonishingly progressive and well done recording project. It seems that in the beginning only around 5 records were planned with a total of 20 songs. And that the initial idea was to conquer new markets outside of Argentina, like Brazil, the USA and others. In that regard the use of vinyl makes perfectly sense as the format was about to spread from North to South America and it has by nature a better transportability either as flexible and unbreakable records or as tape copies. It also looks like as if the Di Sarli MH-project was not only meant to be distributed “for export” but also as an intercultural exchange where other local artists would share some tracks on the same albums with Carlos Di Sarli.

The initial records, though produced in vinyl, were quite short 7″ records with only 2 tracks per side. Later they would grow to 10″ with 4 tracks per side and by the end of the 1950s, they were edited on a series of 12″ LPs with 6 tracks per side. That’s the contemporary LP-format.

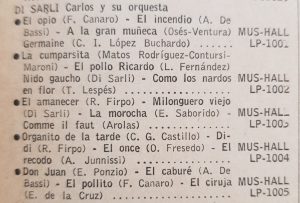

Here is how the original 7″ record series looks like, it’s the very first record, LP-1001. The size is what we know later as 45-rpm singles but these were dobles, 2 tracks per side in 33,33-rpm speed:

- 1st generation vinyl LP-1001 7″ LP 1952

- Back cover LP-1001

- LP-1001 A

- LP-1001 B

It took me some time to understand that these small vinyl dobles were the original releases. In the beginning I was thinking they were later reissues and that vinyl record production started some years later in Argentina (see my previous articles). This was really a big surprise to find out, that these were actually the very first tango vinyls ever produced in Argentina!

See here for the interview which back in 1951 must very much have been a scoop in the Argentine music industry.

Carlos Di Sarli records his first ‘long-playing’ record

A report by Xavier Rouge

Being a reporter for a record magazine has its laps. The reading public is very demanding and wants to be informed of all the novelties of the recording industry. And this is a very interesting novelty. It’s about our first Argentine artist to be recorded on vinyl: Carlos Di Sarli.

We are heading to the studios of Argentina Sono Film, and we meet with Carlos Di Sarli, who is rehearsing at the front of his orchestra before definitively impressing the fonomagnetic tape that will later be poured into L.P. He stops with his activities, and taking advantage of the rest, we hasten to interview him.

“How was the idea of recording on ‘long-playing’ born?” We asked.

“How was the idea of recording on ‘long-playing’ born?” We asked.

“When an Argentine orchestra travels abroad, it usually gets a warm and successful welcome, this means that Argentine music is very much appreciated. So why not record it on ‘long-playing’ albums, so that our authors and musicians are known by all audiences in the world? That’s how the idea was born.”

“Yes, but there are no ‘long-playing’ record factories in our country yet.” We said.

“That was solved in the following way: we record in the studies of Sono Film onto fonomagnetic tape, that later is sent to the United States, where it is formed into ‘long-playing’ records.”

“I’m going to give you another interesting detail,” he adds, “As ‘long-playing’ records bring together several compositions, 40% of their surface is dedicated to the national music of the country to which they are directed, and the remaining 60% is occupied by Argentine music. That is, if the discs are directed to Brazil, for example, the percentage is distributed in choros sambas, marchinhas and in between tangos, milongas and waltzes.”

“What are the compositions you have chosen for the phonoelectric recording?”

“We have made a selection of twenty pieces, among which are: El organito de la tarde, Didi, El 11, El recodo, Don Juan, El caburé, Nido gaucho, Como los nardos en flor, El pollito, El ciruja, and others that I do not remember right now. These are the titles of the típica music part but I can advance you that I will share the responsibility of recording with artists of the stature of Giácomo Rondinella and Sagi Vela.”

“Must we wait long before we can appreciate these recordings?”

“At the moment, two representatives of Music-Hall are in the United States, finalizing the preparations to launch on the market the first series that might be appreciated by the public.”

“In fact,” we said, “this is also for you a comeback to the world of the record, because you didn’t record in a long time.”

“Effectively, and I am already excited to hear the final version poured into the plastic. Okay, guys, I’m sorry to have to interrupt this friendly talk, but we must continue rehearsing.”

We say goodbye with a handshake, and we leave with the pleasant feeling of knowing that we have now our own ‘long-playing’ recordings.

Revista Discomania, Buenos Aires, December 1951, pp. 42-43

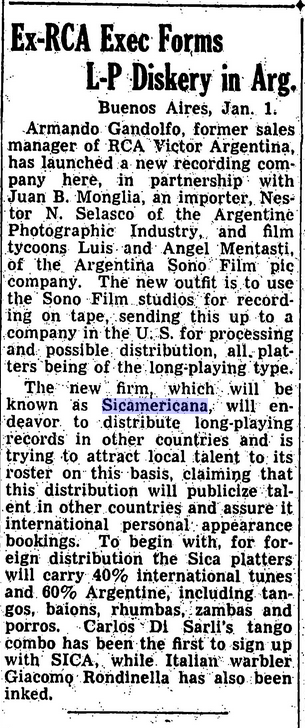

Variety International, Jan. 1952 Issue. The founder of the Music-Hall label, Armando Gandolfo was an ex-RCA sales manager!

In the end, this ambitious project was downscaled and records were mainly sold in Argentina and Uruguay (there licenced to the local label Sondor). The recordings were made on tape in the studios of Argentina Sono Film in Buenos Aires in a magnificent recording room as Discomania states, and were then sent to the vinyl plant in Peru where the records were produced and sent back to Argentina for domestic distribution. It could be that the stampers were produced elsewhere, like i.e. the USA. While I was looking at the original releases, I recognised that on the later records an alternative recording location is indicated on the record label: “Grabado en los estudios de Radio Splendid“, it can be verified on LP-1026, LP-1042 and LP-1050. This strongly suggests that they stopped using the Sono Film recording studio for the last records and that the final 24 MH Di Sarli titels were recorded at Splendid’s studios as a replacement.

In March 1953, Juan Bautista Monglia sells his shares of Sicamericana, the commercial entity behind Music-Hall, to Héctor Noberto Selasco. This makes Selasco the strongest shareholder and manager of the company. When the articles of association were first published in March 1952, Juan Bautista Monglia, Héctor Noberto Selasco and Armando Gandolfo, ex-RCA Victor sales manager, all had an equal share in the company. There is actually a coincidence between the capital restructuring of the company, and the changing of the recording studio. On the first record covers Argentina Sono Film was indicated as “productora asociada” of Sicamericana S.R.L. and it seems that they stopped the coproduction when Sicamericana shrinked to a hierarchical one boss structure. By the way, Wikipedia mentions that only two years later in 1955, Lucas and Atilio Mentasti owners of Argentina Sono Film were being arrested during the Liberating Revolution (Revolución Libertadora) which ended the second presidential term of Peron therefore there could be also political circumstances involved which left the Sono Film studios impracticable.

It’s important to mention that the Music-Hall project was very progressive and probably achieved the first Argentine commercial recording with a reel-to-reel tape recorder and a resulting vinyl record production. It’s still in mono but the tape master brings a new flexibility and mobility into the recording process. The studio and the record plant can now be easily at different remote locations.

At a later period, after the maestro’s departure, some of the Di Sarli MH records were also commercialised in Brazil and Japan but without the announced guest artists. Music-Hall licenced the repertoire to the Sinter label in Brazil and to Seven Seas in Japan.

- 10″ series Brazil mid-1950s

- 10″ series Brazil

- 12″ LP Japan 1967

- 12″ LP Japan

- 12″ LP Japan

Export MH records, produced in Brazil (Sinter label) and Japan (Seven Seas)

While rethinking the business model from export to a mainly domestic distribution, the whole 33-rpm vinyl format turned out to be a burden for the Music-Hall label as most of the record players in Argentina still had one speed in the beginning of the 1950s: 78-rpm. Only the new record players had 3 speeds and who would buy a new record player just to listen to Di Sarli? In order to get a better market penetration, in a later phase of the project, a lot of hybrid records were therefore produced from the same titles to achieve backwards compatibility. That’s around the same time when Odeon and RCA themselves launched their own dual distributions: on 78-rpm shellacs and at the same time on the new vinyl format. The first 78-rpm Di Sarli Music-Hall edition was published on the 26.11.1952 and is a very curious hybrid because it was in the format of a 7″ record running at 78-rpm speed and pressed in vinyl!

The first 78-rpm re-edition was made on 7″ vinyl, this is record 15001, Tangueando te quiero – Quien te iguala, issued on the 26.11.1952 on blue marbled vinyl. They mention on the cover “78 Velocidad normal”

From the last recordings, LP-1050 (only 750 pressed copies), LP-1070 (pressed also as disco 4011 at 1540 copies), LP-1079 and LP-1085, it seems nowadays impossible to find any 7″ vinyl copies. During the last moments of their collaboration with Di Sarli, Music-Hall went massively back to a more conventional support, the classic 78-rpm shellac. It looks as if the vinyls LP-1070, LP-1079 and LP-1085 were issued in very low quantity! This is also standing to reason because from these last 3 vinyl records I have never seen a single picture. According to my research, LP-1070, was also published with a different record number and on a different support, as disco n° 4011 on a doble 78-rpm shellac. So there might be another chance to get these difficult to find titles on this shellac series:

- 4000 series, 4010-A

- 4000 series, 4010-B

The 4000 series was actually produced as 78-rpm shellac records with 2 tracks per side, another curiosity! At least LP-1070 was (re)-issued as record 4011, which is a 78-rpm shellac doble. The 4000 series had a yellow label.

The first MH Di Sarli vinyl records were initially published at very high numbers, at an average of around 14000 ex. And were then gradually reduced to 5000 ex. since the vinyl record number LP-1010, the 10th record, and ending with a very small-circulation of 2000-750 ex. or even less for the last vinyl records! The numbers of produced copies were published in the Boletín Oficial which contains the mandatory legal deposit of every domestic publication. Though I couldn’t find any publication of the release dates for the last 3 vinyls but this is maybe related to some missing Boletíns of the year 1954 in the archives.

As an overall evaluation I would like to mention that these 84 Di Sarli Music-Hall recordings were all very well done, they sound great, especially the original 7″ vinyls. When you listen to a well-preserved copy, you get indeed the impression that the maestro himself is descending from the heavens, MH themselves called their sound fidelity equal to reality, fidelidad que iguala a la realidad. This high sound quality is though not always maintained on later vinyl re-editions, especially the 12″ vinyls often have less good sound. They partly messed up the original equalisation and added on the latest generation LPs some reverberation. There are also some strange problems with the gain where the sound engineer started the transfer too loud and corrected the gain only later after the first bars. On the earlier 10″ and 12″ vinyls there is very muffled sound on some tracks which are therefore virtually useless. A few tracks on these next generation vinyl transfers are OK. Also positive to mention, I didn’t recognise any pitch/speed problems on the following generation vinyl transfers like one sadly often hears with other record labels.

- 12″ LP MH-12016

- 12″ LP MH-12017

- 12″ LP MH-12018

- 12″ LP MH-12019

- 12″ LP MH-12020

- 12″ LP MH-12021

- Tracklisting

On the first 12″ MH LP series from around 1958, 12 of the 84 total tracks are missing, as if one 12″ LP record was never produced (at least I haven’t seen it and I think it doesn’t exist). This is often an indicator that the record label didn’t find back their own material when they prepared for a re-edition years later …

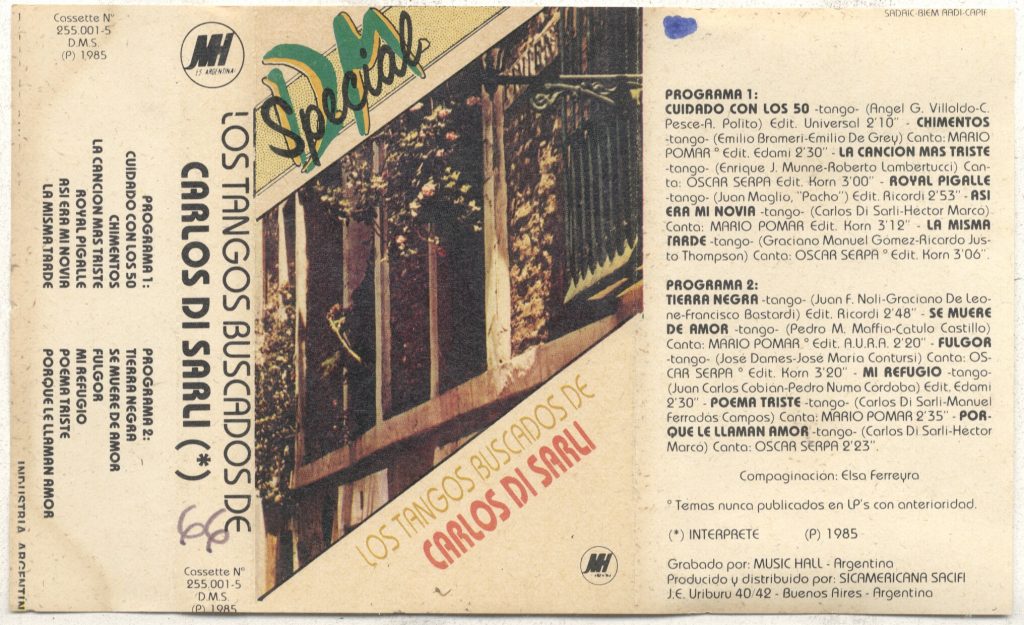

Los Tangos Buscandos de Carlos Di Sarli, Compact cassette Music-Hall 255.001-5 D.M.S. published in 1985

In 1985 Music-Hall issued a compact cassette and on the inlay they marked some titles with the mention “° Temas nunca publicados en LPs con anterioridad”, titles never published on a later LP transfer. Some of these titles are among the hard to find: La misma tarde, Fulgor, Chimentos and Se muere de amor.

The downscaling o f the initially ambitious project and the too early adoption of vinyl for the domestic market with all the resulting problems might have contributed why Carlos Di Sarli returned by the beginning of 1954 to RCA Victor. It could also be related to the change of the recording studio, the last 24 recordings were produced at the studios of Radio Splendid. But maybe it was just the end of their contract. There is a lot to speculate which is favored by the circumstance that the initial distribution of Music-Hall seems rather experimental based on a trail and error method. Discomania shows him in their August 1954 edition as to be back at the RCA Victor studios without mentioning any further motives for the change.

f the initially ambitious project and the too early adoption of vinyl for the domestic market with all the resulting problems might have contributed why Carlos Di Sarli returned by the beginning of 1954 to RCA Victor. It could also be related to the change of the recording studio, the last 24 recordings were produced at the studios of Radio Splendid. But maybe it was just the end of their contract. There is a lot to speculate which is favored by the circumstance that the initial distribution of Music-Hall seems rather experimental based on a trail and error method. Discomania shows him in their August 1954 edition as to be back at the RCA Victor studios without mentioning any further motives for the change.

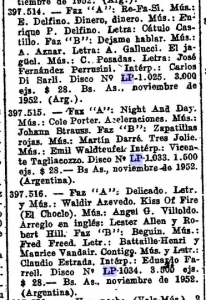

Concerning the concept of guest artists, finally, the 7″ vinyl series has numbering discontinuities when we check the discography. During the first 10 records the numbers were all used for Carlos Di Sarli and then there are holes. These missing record numbers were actually used for other artists and genres, like Cole Porter (LP-1033), Herbert ‘Happy’ Lawson (LP-1044) and a lot more. The Giácomo Rondinella and Luis Sagi-Vela recordings were running on a separate record number prefix in order to distinguish the classical music aspect, the LP-5000 series. The LP-1000-series was initially the popular music classification. All these recordings were never published together on a shared record like the initial idea proposed but were juxtaposed on separate records.

- From Boletín Oficial

- From Boletín Oficial

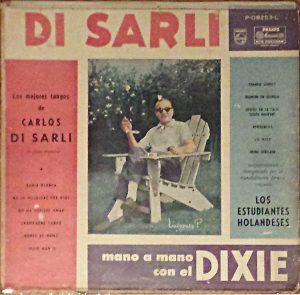

It’s much later that Carlos Di Sarli recorded an LP album alongside with another artist. By then he had long left MH and after some years at RCA Victor he joined the Philips label during his last recording sessions with the orchestra. This shared record was published in 1960 and it’s called Carlos Di Sarli mano a mano con el Dixie. Los Estudiantes Holandeses are also known as the Dutch College Swing Band. The record contains a succession of one track by Di Sarli and one swing orchestra track, in ping-pong battle mode, all recorded in a (fake sounding) live environment. In the end his idea of an intercultural concept became a reality!

As we can see now from our future perspective the high goals of the initial Music-Hall project were flattened and a compromise was found. The recordings were nearly exclusively distributed in Argentina and Uruguay and the guest artist concept abandoned. Instead of exporting Argentine titles to the rest of the world, mostly foreign artists were imported into the domestic record market via Music-Hall. The maestro delivered fantastic recordings but they didn’t find any major international resonance back in the days. How would he be delighted to see that nowadays his music is played globally!

As we can see now from our future perspective the high goals of the initial Music-Hall project were flattened and a compromise was found. The recordings were nearly exclusively distributed in Argentina and Uruguay and the guest artist concept abandoned. Instead of exporting Argentine titles to the rest of the world, mostly foreign artists were imported into the domestic record market via Music-Hall. The maestro delivered fantastic recordings but they didn’t find any major international resonance back in the days. How would he be delighted to see that nowadays his music is played globally!

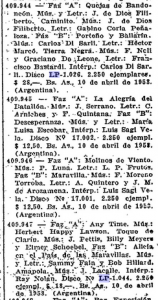

Advertisements from the launch of the new MH label in the revue Discomania

And last but not least, see here for a visual succession of the main Music Hall vinyl generations, from the first issue starting in 1952 to the last LP edition from the 1980s. The reverberation was added on some tracks since the 1979 edition. And the edition El señor del tango, red and green/blue monochrome cover, is a reduced two volumes edition, focusing on the most known initial titles.

- 1st generation vinyl LP-1001 7″ LP 1952

- 2nd generation vinyl MH-8006 10″ LP 1955

- 3rd generation vinyl MH-12016 12″ LP 1958

- 4th generation vinyl MH-12.105 12″ LP

- 5th generation vinyl MH-90.873-9 12″ LP 1979

Based on my research I have put together a discography of Carlos Di Sarli’s Music-Hall recordings. It’s still a work in progress and based on records which are in my collection. The recording dates which are taken from the later CTA CD edition are very questionable and some aspects of the way the last MH recordings were issued are still unclear. The CTA dates are questionable especially when the release date, which implied a legal deposit of 3 physical records at the national archive, is before the recording date, that’s implausible! I would like to get access to the data of the Music-Hall recording book, and as, they used reel-to-reel tape masters for the recordings, the tape boxes might contain the take info and also the recording dates. So there might be a chance to get hold of the correct dates if these tapes and boxes have survived. But as it looks like these boxes aren’t any more in the heritage of the former Music-Hall company. They must have been lost, maybe during their bankruptcy …

If you want to contribute to this document, if you have suggestions or information to share, please mail me.

![]() Carlos Di Sarli Music-Hall Discography in CSV Format

Carlos Di Sarli Music-Hall Discography in CSV Format

Addendum: Recently, while visiting a friend, he showed me a record from Japan which was issued very close to the original Argentine release date. It’s the same 7″ vinyl format as in Argentina. It is very likely that CTA’s reissue of the Carlos Di Sarli Music-Hall recordings is based on that series. This shows that MH had a much earlier international exchange than I was initially thinking. That could also explain certain questions which were raised concerning the last 3 records which have never been seen and might therefore likely to have ever been published. Maybe the whole series has been published in Japan on Mercury Records Japan in their DD-300 reprint! Interestingly they are in 45-rpm (the Argentine series is in 33.33-rpm speed) which means they were most likely transferred anew from MH reel-to-reel tape copies sent to Japan.