In the elder days of the tango, but also in other genres of the time, the singer’s role has been considered to be no more than that of another instrument. Estonishingly the early singers somehow camouflage into the line of the other instruments of the orchestra. This has been the fashion during the 1920’s and the 1930’s in all sorts of dance orchestras not only in tango. And it still exists nowadays in what is called backing vocals. Often the singer was recruited amongst the musicians of the band and would sing an extended chorus, entering quite late into the performance, around the second chorus or even later. And just because of this short and late appearance, he remained in the background of our perception. It happened that I danced a beautiful tango with refrain singing and asked my partner during the cortina how she liked the singer and she responded: “Has there been a singer?”

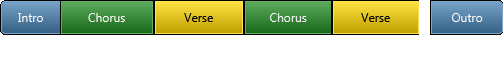

Most of the time tango uses the strophic form of the Kunstlied, where contrasting verse – chorus (refrain) parts alternate, more or less as in the following schema in a binary alteration where each part takes approximately 30 seconds:

Depending on the length of the piece, this scheme might vary or contain more or less parts. So let’s listen to a typical refrain structured tango where the singer enters at the second chorus in the older style refrain singing of the 1920’s and 1930’s:

Tipíca Enrique Santos Discépolo con Tania (estribillo/refrain style), Desencanto, 1937

Here are the main formal characteristics of the estribillo or refrain style of singing:

- Entry of the singer at the second chorus, +/- at minute 1:30, or later

- Singing the refrain or an increased refrain

I have chosen this example because the same orchestra, Enrique Santos Discépolo, recorded the same title twice, once in estribillo style (refrain singing) and a second time where all the lyrics are presented (tango canción).

Tipíca Enrique Santos Discépolo con Tania (canción style), Desencanto, 1937

This last example represents yet another style of singing as you can recognise. It’s not estribillo style but tango canción. Tania, Discépolo’s wife, has been a very famous singer and actor, a tango diva, who just starred in the movie “El pobre Pérez“. These two recordings of the tango Desencanto were made on the 1st February 1937, just a couple of days before the public release of the movie. These records were therefore a kind of early soundtrack issued to cash in on the eventual success of the movie. In the second recording the orchestra starts with a reduced intro and immediately backs off into accompaniment. This let’s the singer enter into the performance and the orchestra then gently follows her voice quasi solely imitating the rubato of the voice at a considerably lower loudness to let the singer shine in the forefront. This genre had a long tradition with the cantor nacional, like Carlos Gardel, Ignacio Corcini, Agustín Magaldi, Charlo, Alberto Gómez, Agustín Irusta, Roberto Díaz and many others and still is very present nowadays. I’m thinking about the legendary Alberto Podestá who still today appears in public, accompanied just by some musicians. The biggest historical star of the tango canción genre has certainly been Carlos Gardel who’s discography is nearly exclusively composed of canción titles. With tango canción, the accompaniment is often done with guitars and the aim is to listen to the song carried by the beautiful voice of the singer. It is a purely recital presentation of the complete song lyrics, less suited for dancing and more aimed for listening and contemplating. Whereas the estribillo version of this recording is the presentation you will hear at the milonga because it’s better suited for dancers as it has a steadier and faster tempo and another balance between the singing and the orchestration. If you are a tango DJ, you should be aware of these different kinds of song interpretations.

This last example represents yet another style of singing as you can recognise. It’s not estribillo style but tango canción. Tania, Discépolo’s wife, has been a very famous singer and actor, a tango diva, who just starred in the movie “El pobre Pérez“. These two recordings of the tango Desencanto were made on the 1st February 1937, just a couple of days before the public release of the movie. These records were therefore a kind of early soundtrack issued to cash in on the eventual success of the movie. In the second recording the orchestra starts with a reduced intro and immediately backs off into accompaniment. This let’s the singer enter into the performance and the orchestra then gently follows her voice quasi solely imitating the rubato of the voice at a considerably lower loudness to let the singer shine in the forefront. This genre had a long tradition with the cantor nacional, like Carlos Gardel, Ignacio Corcini, Agustín Magaldi, Charlo, Alberto Gómez, Agustín Irusta, Roberto Díaz and many others and still is very present nowadays. I’m thinking about the legendary Alberto Podestá who still today appears in public, accompanied just by some musicians. The biggest historical star of the tango canción genre has certainly been Carlos Gardel who’s discography is nearly exclusively composed of canción titles. With tango canción, the accompaniment is often done with guitars and the aim is to listen to the song carried by the beautiful voice of the singer. It is a purely recital presentation of the complete song lyrics, less suited for dancing and more aimed for listening and contemplating. Whereas the estribillo version of this recording is the presentation you will hear at the milonga because it’s better suited for dancers as it has a steadier and faster tempo and another balance between the singing and the orchestration. If you are a tango DJ, you should be aware of these different kinds of song interpretations.

On canción recordings the name of the singer is written in big letters and mentioned first on the label of the records. Often the name of the orchestra or the guitar players are not given (in the database at tango.info you therefore might see the mention –unspecified guitars or –unspecified orquestra). Whereas on the estribillo recordings, the orquestra is mentioned first and the singer second, like in the current example “Estribillo cantado por Tania“. But sometimes the refrain singer wasn’t mentioned at all and replaced with the words “Con estribillo” (in some meta databases you might therefore find the mention –unspecified male|female singer). To sum up: On the tango recordings with refrain singer, estribillista, the singer wasn’t considered as very important, and given only sparse credit, on the opposite, when the singer presented the tango in tango canción style, he was considered back then to be the most important performer.

The tango canción genre certainly found its climax in the mid-1930s incarnated by Carlos Gardel, the most prominent figure in the history of tango. “Gardel’s baritone voice and the dramatic phrasing of his lyrics made miniature masterpieces of his hundreds of three-minute tango recordings.” [Wikipedia]

Carlos Gardel played a very important precursor role and is known as the first tango singer. Let’s see how he earned this titel: Mi noche triste has been composed in 1915 by Samuel Castriota in Buenos Aires without lyrics. His instrumental version was called Lita. It was Pascual Contursi who later wrote the lyrics to this tango in Montevideo and Gardel, who liked it, performed this combined Castriota-Contursi vocal version in January 1917 in Buenos Aires. This is the first time that a tango received sentimental lyrics with a sad character fitting the music. Now all of a sudden, poetry and singing had been added to tango. If we check the discography of the important tango orquestras around that time, we can see that their whole production had been instrumental! Canaro and Firpo were struggeling to find new and more satisfying forms for the tango orchestra and the tango genre was developping its instrumental foundations, violins were added to counter balance the loudness of the newly arrived piano (Firpo), a little later the doublebass found its entry into the tipica (Canaro) but nobody had a singer. The tango Mi noche triste is considered to be the birthplace of the sung tango.

Now, lyrics weren’t completly unknown to the Guardia vieja, there are several recordings by Villoldo and others which testify this. But their music was faster and these lyrics missed the sentimental component, they were happy, sometimes burlesque or even vulgar. Also Gardel himself performed until then a folk repertoire which was composed of “Estilios”, “Tonadas” and “Milongas camperas”. When Gardel performed Mi noche triste, the tempo of the tango orchestras had slowed down and this tango hit the community with a huge impact and a new form of identification through the lyrics which were perfectly in sync with the tempo of the music! The title is program and we can see that there is a first person narrator and a plot with a beginning and an end. Somehow a very short story. This kind of narrative voice is very common for most of the tango texts which would follow. Full lyrics of Mi noche triste.

Without any doubt, as he confirms himself in his auto-biography, influenced by Gardel, 1917 is also the year when Francisco Canaro composed and recorded the first tango with a song himself called Cara sucia, cantado por Arturo Calderilla. It’s a transcript of an elder tango composed in 1884 by Casimiro Alcorta, el Negro Casimiro. Interestingly, this tango was known before under the title of Concha sucia, After some initial experiments the sung tango became more and more frequent in the orquesta típica and was generalised and in equal production compared to instrumental tangos at around the year 1928. Francisco Canaro later reflects this change in his auto-biography [Mis Memorias, 1957, p. 168]: “Always being demanding with myself, I didn’t feel satisfied and it seemed that to my records and the orchestra that, meanwhile, already it had been increased in the number of musicians, they needed something and were not yet complete: they needed a vocal part, that is to say, the singer.”

[Mis Memorias, 1957, p.177]: “In my long artistic trajectory I had the following singers in my orchester: Roberto Díaz, with whom I initiated for the first time on record refrain style singing for a tango composed by my brother Mario called: ‘Así es el Mundo‘ […]” This recording by Francisco Canaro of a first refrain style singing was made in 1926 and has the Odeon record number 4155B, technically still an acoustic recording but the starting point of a new style of singing derived from the canción genre. Interestingly, we can therefore date the usage of refrain singing in tango just at the transition to the electrical recording process which was introduced just a couple of months later in Argentina in 1926.

On 24th June 1935, Carlos Gardel, died tragically. Such was Gardel’s prominence in Tango music that his sudden death left a void, but that was to change. Precisely 8 days after this sad event, Juan D’Arienzo entered the recording studio, signing an initially short contract with the Victor label for a series of instrumental themes.

If we take apart the vals and milonga recordings of Juan D’Arienzo in his pre-1940’s phase, there is one tango recorded with Enrique Carbel, Paciencia, and 14 tangos with Alberto Echagüe and it’s impossible to say that these recordings remained in the purest estribillo tradition of singing. We are about to enter into a transition period!

During this transition period which lasted from around 1937 to 1941, the role of the singer started to change again, more and more the singer presents at least two strophes of the song and sometimes he even comes back in the outro to finish the tango together with the orchestra. Later in the 1940’s a singer would even deliver the complete lyrics without therefore drifting necessarily into the tango canción genre. There has been nevertheless a general trend in tango starting towards the end of the 1940’s to a more recital, concert style with some orchestras as the public lost more and more interest in the dance. Check out the following example of a late 1940’s recording of the before mentioned tango Desencanto recorded by singer Alberto Marino. This recording dates from his beginning solo career. It has been recorded shortly after he left Aníbal Troilo’s orchestra:

Alberto Marino, Desencanto, 1947, (presenting the complete lyrics)

Here are the main characteristics of the new cantor de orquesta style of singing:

- Entry of the singer at the first strophe, +/- at minute 1:00

- Singing at least 2 strophes of the song (not just an increased refrain)

- Optional: Reentering of the singer in the outro to finish the tango together with the orchestra

The orchestras of the 1940’s, like the newly formed orchestra of Aníbal Troilo with its singer Francisco Fiorentino immediately integrated this style in their repertoire at least at their first recording sessions in 1941. Fiorentino himself started off as a bandoneon player in the late 1920’s and was asked to do estribillo for the bands from time to time. And he later became such an important singer with a solo carrière in the end. By the way, Todotango.com mentions Francisco Fiorentino in a very interesting article as to be the first glance of a cantor de orquesta:

En 1934, siendo estribillista de la orquesta de Roberto Zerrillo, produce el singular hecho de cantar un tango con la letra completa en la grabación del tema “Serenata de amor” del propio Zerrillo y Oreste Cúfaro. Se vislumbra el fin de la “era de los estribillistas” para dar paso a la nueva etapa de “los cantores de orquesta”.

Oreste Cúfaro, Roberto Zerrillo con Francisco Fiorentino, Serenata de amor, 1934

Some say D’Arienzo stuck to the old scheme and reserved therefore a reduced role to the singer to remain himself the most important star of his orchestra. There is though at least one recording where this isn’t the case, it’s in the movie “Melodias Porteñas“ from 17th November 1937, interestingly also a tango composed by Enrique Santos Discépolo. Here Echagüe is singing surprisingly in pure cantor de orquesta style the tango Melodías Porteñas. Impossible to say if this form had been influenced by Troilo whose band just started to perform with Fiorentino in the summer of 1937. This is because Troilo didn’t have a chance to record anything yet. So we don’t know for certain how the Troilo – Fiorentino’s lyrics might have sounded that year …

It seems also that in this situation Juan D’Arienzo didn’t dominate the recording market yet because the soundtrack of the movie “Melodías Porteñas” hasn’t been done by his orchestra, but again, was sung by Tania accompanied by Enrique Santos Discépolo’s own orchestra as you can see in the image to the left. Without any doubt the relation between Enrique Santos Discépolo and the Víctor company had been sealed with a precise recording contract. Don’t forget that Juan D’Arienzo was already under contract at the same record label but never recorded his version of Melodías Porteñas with Alberto Echagüe. He recorded only an instrumental version on the 21st December 1937. Whereas Tania’s version had been on the market already on the 9th November 1937, exactly 8 days before the release of the movie!

Analysing the other bands’ repertoire shows nevertheless that the form of the cantor de orquestra existed in an embryonic form since much earlier, listen to the following recording of Alma by Adolfo Carabelli with the singer Alberto Gómez. It anticipates some formal elements of the cantor de orquestra singing style already back in 1932, it is still missing a second sung strophe but it has the entry at the first chorus and the optional element of the singer coming back to prepare the ending of the tango together with the orchestra:

Adolfo Carabelli con Alberto Gómez, Alma, 1932

The return of the singer in the outro, is also present in several Francisco Lomutu recordings with Jorge Omar and Fernando Díaz, like Monotonía, 1936, No cantes ese tango, 1937 or Propina, 1934, etc.

In the Donato repertoire you can find a lot of recordings which give a more important role to the singer and you could qualify some of them as to be in perfect cantor de orquestra style. As if Donato refused the fashion of the refrain singer, setting his own trends. Listen to his recording of Madame Ivonne with the same Alberto Gómez from 1935:

Edgardo Donato con Alberto Gómez, Madame Ivonne, 1935

And if we have a look at what’s happening in Paris at around the same time we can see the same shift to more song in the danse music when we approach the end of the 1930’s. Compare these two versions of Campanas del recuerdo one by Rafael Canaro and the other by Manuel Pizarro recorded in the same year:

Rafael Canaro con Ricardo Duarte, Campanas del recuerdo, 1936

Manuel Pizarro con Manuel Pizarro, Campanas del recuerdo, 1936

Where Pizarro sticks to the older fashion of the estribillista, Rafael Canaro presents a nearly full blown cantor de orquestra! The Francisco Canaro repertoire with singer Roberto Maida is also spiced up with this more present role of the singer. Check out their version of Desencanto and compare it to Tania’s recording with Discépolo. Where Tania remained in estribillo tradition, Maida presents 2 strophes of the song:

Francisco Canaro con Roberto Maida, Desencanto, 1937

There has been undeniably an evolution which let to the music of the 1940’s and the new understanding of the singer. Nobody in particular invented this singing style, it just came upon, helped by some early adopters and sparsely spread singular experimental cases. All of its ingredients have been present all along the 1930’s in some blueprint form. It’s also worth to mention that the record labels in the 1940’s were still printed with the words “Tango con estribillo” even if the style has been “cantor de orquestra”. Only in the 1950’s the mention “Canta: …” replaced definitly the word estribillo on the records.

There is though an aspect which cannot be pinpointed and that’s the expression of the singer. In the 1940’s the singing has been more of a celebration of the tango lyrics where the singer would live all of the presented sufferings and feelings once again on stage. Whereas the estribillo singers had a more frivolous, nearly uninvolved, distance to the lyrical plot.

Now I know why I like so much Franscico Canaro’s recordings with Carlos Galán. It’s the gentle singer’s presence which blows some 1940’s modernism into these 1930’s recordings!

This is so interesting!

Thanks for posting!

well researched and very well presented!

Pingback: Bekenntnisse eines spanisch-unkundigen Banausen – mYlonga