“We know, and we cannot explain the cause, that many típicas have recorded up to five versions onto wax, and despite the time elapsed these works have not been released, nor have they gone on sale. And on the other hand, interpreters who were not part of our middle recorded yesterday, and only a few hours after the printing, their records circulate.”

Julio Jorge Nelson, songwriter and tango critic,

Buenos Aires Oct 1951

A new record company is born

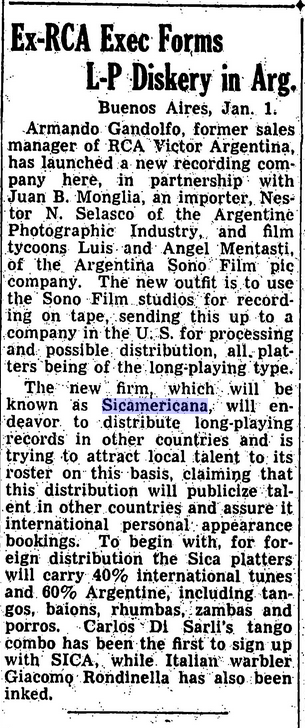

In the beginning of the 1950s something very interesting happened to the Argentine music market which had an important influence on the subsistence of the tango genre. A lot of new record labels were founded multiplying the chances for the tango bands to get a recording contract. To quote just a few: Orfeo (Caló, Firpo, …), Columbia (Fresedo, Pirincho, Charlo), Pathé (Attadia, Pedernera, Del Piano), Pampa (Varela, Barbero, Donato, …), Antar-Telefunken (1957 Uruguay), etc.

This occurred at a moment when more and more foreign music got pushed onto the Argentine music market. It is the post war time and the culturally isolating bubble of the tango golden age had definitively come to an end. The music market evolved more and more into a global business where the record labels would sign international agreements for catalog sharing and representing each other in their respective countries. The recordings had become more transportable since the technology was shifting away from the former shellac process, which was heavier, less flexible and slower in production, to the new vinyl technology. This opening of the music market represented a chance and a danger at the same time. On the one hand, the sudden availability of global markets and the diversification of national record labels was an opportunity to be sized by the numerous tango musicians, maybe also to get exported and on the other hand, the local market was submerged by foreign music shifting away the public interest from the music of the típicas.

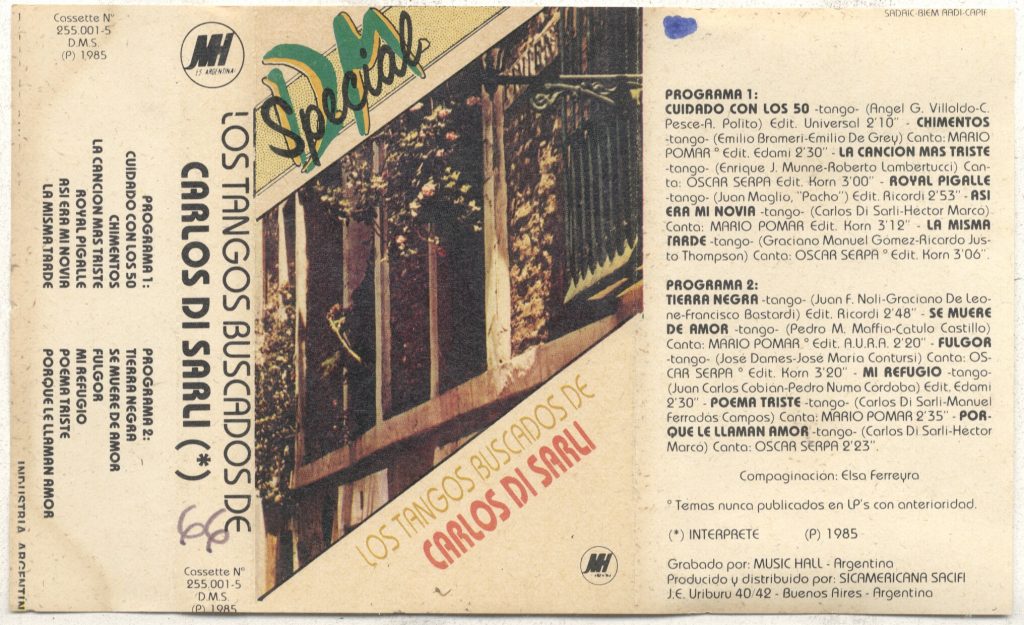

One of the new labels founded in Buenos Aires was Music-Hall, my last article was discussing this label in depth, the present article will focus on the other tango related independent record company called Discos T.K.

of the new labels founded in Buenos Aires was Music-Hall, my last article was discussing this label in depth, the present article will focus on the other tango related independent record company called Discos T.K.

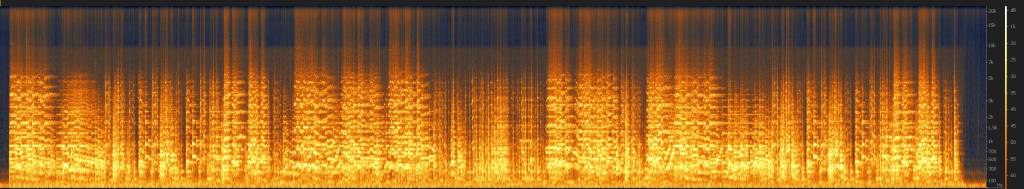

While Music-Hall intensively and right from the beginning was working with the new vinyl technology, the TK label which started issuing at around the same time at the beginning of 1951, decided to work with the older shellac process. As discussed in my last article, Music-Hall, the other competing record label, had problems being an early adopter of vinyl because nearly nobody had yet a vinyl record player! TK certainly had better compatibility but their main problem was bad sound! And indeed, while listening through the original TK shellac records I sadly confirm that the quality of their first recordings is deficient, whereas, and that’s important to remind, the recording quality of Music-Hall was extremely high during their whole production history! As we will see, TK went through some kind of learning process which finally would improve their sound but for the Aníbal Troilo series which I will discuss here, it improved indeed but it never became perfect.

Often these two new labels are quoted or discussed as to be a single entity by error! People easily mix them up. But they were actually two completely separated commercial companies and competitors! The confusion might come from the fact that in the mid-1960s TK’s catalog was merged into Music-Hall.

Inter-Bas, the company behind TK

Music-Hall wa s owned by the company Sicamericana S.R.L. (Sociedad de Responsabilidad Limitada) and Discos T.K. was owned by Inter-Bas S.A. (Sociedad Anónima or Sociedad por Acciones). This is a form of company where originally, shareholders could be literally anonymous and collect dividends by surrendering coupons attached to their share certificates.

s owned by the company Sicamericana S.R.L. (Sociedad de Responsabilidad Limitada) and Discos T.K. was owned by Inter-Bas S.A. (Sociedad Anónima or Sociedad por Acciones). This is a form of company where originally, shareholders could be literally anonymous and collect dividends by surrendering coupons attached to their share certificates.

The founding act of Inter-Bas S.A. dates back to 27.9.1946 and in the beginning it was described as a stationary business dealing with office supplies, print media and typewriters. The brand name was registered by a certain Leonardo José Vidal.

In December 19 50, Inter-Bas takes over a company which is specialised in selling equipment for learning English at home. During this act the name of another associate is mentioned: Eduardo Botta.

50, Inter-Bas takes over a company which is specialised in selling equipment for learning English at home. During this act the name of another associate is mentioned: Eduardo Botta.

And in 1951 Leonardo José Vidal files a patent for a portable book record holder and is mentioned as the General Director of Inter-Bas S.A.

Processing just this information, it looks like besides entering into the music business, the company was interested in developing a multimedia device for audio language courses. We later will see that the invention of this patented device is actually key in understanding the brand name T.K.!

What does TK mean and stand for?

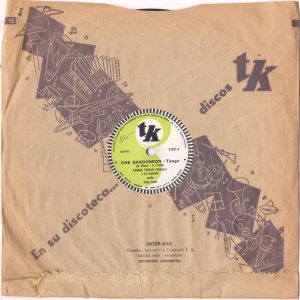

En su discoteca… Discos TK / Inter-Bas Cientifica, Industrial & Comercial S.A. / BUENOS AIRES ARGENTINA / INDUSTRIA ARGENTINA

The name TK is literally explained on the record jackets. In 1951 records didn’t have yet sophisticated covers, shellac records used to be wrapped into kraft paper which often contained a form of simple printing. On the TK series there are outline drawings of instruments with some geometric shapes crossing the jacket. The other crossing line is the Spanish sentence “En su discoteca … discos tk” ending in the logotype of TK. From this we can derive one meaning of the letter combination TK: It is the homophone of the Spanish word teca and together with the word discos, discos TK, simply means discoteca. This word has three meanings: 1. a record library, 2. a device or furniture to store records and 3. a public dancing club. In some online forums there are contributions which speculate that TK might stand for Troilo-Kaplún. During my research I couldn’t find any evidence for that or that Aníbal Troilo or Raúl Kaplún were commercially involved in the record company other than having signed a recording contract with it.

The second meaning of the word discoteca, a device or furniture to store records, matches actually the patent which the director of Inter-Bas S.A. Leonardo José Vidal filed internationally! (see above) I can easily imagine that he came up with the name Disco TK, discoteca, to have an interesting name for his new practical storage device being at the same time a furniture and a collection device for records (disco) and books (biblioteca), compound and with an added neologism it results in name Disco T.K. And indeed, Inter-Bas had been a pioneer in the field of audiobooks, a chapter in their company history which seems to be forgotten and this perfectly fits the brand name Disco T.K. The advertisement for their audiobooks, to the left, published in 1951 is still under the company name of Inter-Bas without the new strong double articulated brand name which reflects the concept of publishing spoken books!

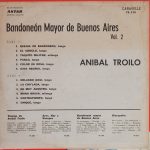

The first published tango records

TK started off the record production with very well known musicians when they published their first bunch of records in 1951. Among the first signed artists were the tango diva Mercedes Simone, the soloist Agustín Irusta, the Orquesta Hawaiian Serenaders, the Orquesta Astor Piazzolla, and others. Later TK added more artists to their catalog like Horacio Salgán, Tito Martin, Joaquin Do Reyes to quote just a few. With Raúl Kaplún TK recorded only 4 records in total! With Aníbal Troilo they produced a total of 49 shellac records. Normally on a shellac record there are two tracks which should add up to an even total but with the TK-Troilo recordings there strangely is only an impair grand total of 97 tracks. This is because they have added the same recording of the milonga La trampera on two different records. Once on the record TK-S-5038 together with the tango N.P. and another time on the record TK-S-5057 alongside with the vals Un momento. On both records the matrix number of La trampera is 84/51. The faithful Troilo fan must have felt cheated when discovering that it’s the same track bought twice!

- TK-S-5038-A 84 La trampera

- TK-S-5038-B 85 N.P.

- TK-S-5057-A 126 Un momento

- TK-S-5057-B 84 La trampera

TK sold La trampera twice, once on the record S-5038 with N.P. and then a second time some months later on the record S-5057 with the vals Un momento. Both versions of La trampera are the same and they do have the same matrix number!

The first troilo TK record, Che Bandoneón – Para lucirse

Unlike Music-Hall, TK had an incredibly rich output already during its beginning phase. They were issuing new records nearly at the same pace as the big players Odeon and RCA Victor!

- TK-S-5001-A Che Bandoneón

- TK-S-5001-B Para lucirse

- Typical 78-rpm record jacket

It’s in March 1951 that the first Troilo TK record was issued to the public. It had the number Disco T.K. S-5001. (As a side note: It’s the first record number of TK but not the first matrix number) On the A side Che Bandoneón and on the B side Para Lucirse interpreted by Aníbal Troilo and his orchestra. This record is very programmatic as the A-side is composed by Troilo himself and on the other side contains a tango by Astor Piazzolla who was since the end of the RCA Victor contract introduced as one of the new arrangers of the band as mentioned in the official Troilo discography. The Piazzolla arrangements and repertoire gave the TK recordings a very avantgarde and recital touch. Some of these tangos can also live outside of a pure dance music context and have an incredible listening factor!

A nice move of TK was that they have put the recording year on the records, not many other record companies did this. In my opinion, the others mainly didn’t mention any dates on records because they wanted to keep the records fresh to the customer. This TK feature helps greatly to organise the records according to their recording year and to disambiguate. On this first record, the recording year is punched into the lead-out groove, check the enlarged picture to the left. Later they would add it on the record label, next to the matrix number.

A nice move of TK was that they have put the recording year on the records, not many other record companies did this. In my opinion, the others mainly didn’t mention any dates on records because they wanted to keep the records fresh to the customer. This TK feature helps greatly to organise the records according to their recording year and to disambiguate. On this first record, the recording year is punched into the lead-out groove, check the enlarged picture to the left. Later they would add it on the record label, next to the matrix number.

As you might have recognised, the graphics on the T.K. record labels was a slightly derived Yin and Yang design, green and white in the beginning of the Troilo series, then for the 12 Troilo-Grela recordings it was black and white and later, for the last recordings it was red and white. This design of divine connotation gives them a touch of far-eastern wisdom and mystery. The outer ring has been printed interestingly with a black and white stroboscopic ring. When illuminated by incandescent or florescent lighting while the record spins on a turntable, the strobe lines will stand still at the appropriate configured speed! It is very possible that the record label transmitted that way the recommended playback speed information.

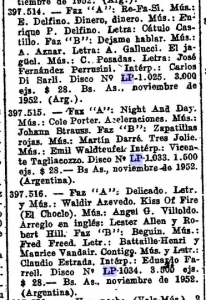

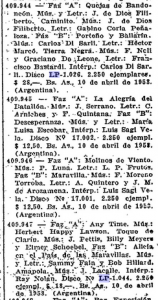

During the editions of the Troilo-TK records, the audiophile Discomania revue was following attentively the label and commented these record issues and artists. Let’s travel through the different highlights and hear how the tango critics back in the days discussed these recordings:

Pick-up #1 Responso-Discepolín, the tribute to the tango poets

- TK-S-5048-A Responso

- TK-S-5048-B Discepolín

On the 3.5.1951 Homero Manzi the famous tango lyricist died. The instrumental tango Responso is Troilo’s farewell to Manzi. Manzi collaborated on numerous tangos with Troilo and both were connected through a deep friendship. The tango an the B-side on this record, Discepolín, is such a Troilo-Manzi collaboration. It’s sadly their last collaboration and a song which Troilo composed as a tribute to Enrique Santos Discepolo and for which Homero Manzi, who was already deadly ill at the time, wrote the lyrics. Posthumous, one can say that this record became a homage record for both tango poets because Enrique Santos Discepolo also died himself at the end of that same year! The lyrics of the tango Discepolín are delivered by the singer Raúl Berón who will be present during most of Troilo’s TK time together with Jorge Casal, they are Troilo’s main singers from his TK period and will stay with the orchestra until around 1954-55.

“Troilo, Anibal (Pichuco) and his orchestra. Responso, Tango (A. Troilo) – Discepolín, tango (H. Manzi-Troilo) (T.K, S-5048). Troilo offers us a magnificent version of his last tango Responso, written in homage to Homero Manzi. There may be excess bandoneon, but it is justified if we understand that the popular director has wanted to express, in notes, his ‘musical tears’ to the definitive absence of the friend of all hours. On the other side of the disc we hear the posthumous page of Homero Manzi, with musical stanzas by the conductor, which is titled Discepolín. The set of Pichuco is shown with the impeccable adjustment of always, and we note also the happy recovery of the singer Raúl Berón.” [Discomania, ed. 1, Oct. 1951]

Pick-up #2 Bien milonga-De vuelta al bulin, Troilo the movie star

- TK-S-5053-A De vuelta al bulin

- TK-S-5053-B Bien milonga

In a side note of Discomania of November 1951 one reads the following concerning the Troilo record TK-S-5053: “Ismael Spitalnik, first retired as bandoneonist, and is now in his new role of arranger for great tango bands. He was the one who collaborated in his double task of composer and arranger so that Troilo will shine once more through the tango called Bien milonga. Piano, bandoneon and strings come together effectively in a recording that deserves to be described as outstanding; then we hear, from the movie Mi noche triste (still unreleased) the tango of José Martinez and Pascual Contursi, De vuelta al bulin. Once again this ratifies Raúl Berón’s solid position as a singer, acquired in the típica of the author of Barrio de tango.” [Discomania ed. 2, Nov. 1951]

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=_hBaKDaYGyQ

“Mi noche triste: was the first premiere of the year (January 3, 1952), directed by Lucas Demare. The movie is a free allusion of Pascual Contursi’s life. Troilo intervenes with his orchestra making incidental music, composed by Lucio Demare. He interprets, Mi noche triste (Lita), which in the fiction is sung by the actor Jorge Salcedo (doubled by Oscar Alonso), Ventanita de arrabal and a fragment of Que querés con esta cara (doubled by Jorge Casal) and also some notes of El porteñito.” [Todotango.com]

Pick-up #3 La cumparsita-Inspiración, the updating of the old guard

- TK-S-5054-A 125 La cumparsita

- TK-S-5054-B 127 Inspiración

“La Cumparsita, the most executed tango in the world, perhaps the only one that is treated differently by each of the orchestras that include it in its repertoire, is offered by Troilo in a different version. Pichuco does not try to show off making the ‘bellows’ cry. The defect that we point out in the other típicas is that according to the instrument played by the director of the ensemble, La Cumparsita is ‘arranged’ (or disarranged) for the director-performer to abuse the solos. In this register, the orchestral equipment is complete, the strings, the piano and the bellows alternate the rhythmic melodies complementing each other perfectly, without special phrases that in most cases only serve to distort the original sense of the score.

Returning to the recording of Troilo, on the other side of the record: Inspiración by violinist Peregrino Paulos, with lyrics written much later by Luis Rubinstein. This tango, had the peculiarity of being composed without lyrics, and was in that form well received by the public. At the time, the melody was forgotten and replaced by other successes, when Rubinstein, years after the composer disappeared, expanded it with his own verses. With these Inspiración made a triumphal comeback to occupy a privileged place among the music of the típicas. The curious thing is that after this initial success it returned or fell another time into oblivion, to reappear, years later, as an exponent of the tangos of the Guardia Vieja, but again without lyrics.” [Discomania, ed. 5, March 1952]

pick-up #4 Tanguango-La violeta, the invention of a new rhythm!

- TK-S-5058-A Tanguango

- TK-S-5058-B La violeta

Here is the ninth Troilo record which had been announced by TK in an advertisement as to be a brand new rhythm, the Tanguango! Maybe you remember, numerous orchestras tried in the past to come up with new rhythms. The most successful was certainly the invention of the milonga of the city (milonga ciudadana) by Sebastian Piana and songwriter Homero Manzi back in 1931. This newly presented rhythm lead to a permanent new tango sub genre to which we still dance today in the modern milongas. Other such new rhythm creations were limited in time like tango rumba or Canaro’s experiences with Tangón-Milongón which found actually a larger adoption in Uruguay. The Tanguango as they called it is in that regard not a dead end. It is indeed very typical of Astor Piazzolla’s music with it’s sometimes shifting rhythms from tango to milonga (candombe in this case) and vise-versa. In this context I remember also the piece Bordoneo y novecientos by Osvaldo Ruggiero which also switches back and forth from milonga to tango. To my big surprise, at a festival some years ago I got myself caught by Stazo Mayor and Alfredo Marcucci performing such a rhythm shifting piece while dancing!

“TANGUANGO, thus capitalized, at the outset this exceptional composition of Astor Piazzolla was quite a headache to the popular Troilo, who came out to break molds with a plausible sense of avantgarde. Not to say that he was vexed or insulted, but if, for the first time, he received an unforgettable ‘whistle and boo’ when he was publicly performing the piece. But, at the second live performance of the Tanguango, Troilo was greeted by those who had hissed him before. With ‘bongo’ and ‘tambora’ and a great orchestra unfolding, Píchuco [Troilo’s nickname] recorded this version in which great and serious hopes are credited. And by sharing them fully, we extend our applause and our adherence to those who, the performing artists and the recording company, have put their soul and their efforts in the achievement of this new manifestation.” [Discomania]

When I was listening for the first time to this record, I had all sorts of associations in my head. Once I was in Africa at the Congo River than it had this modernist character coming after the drum part. It’s crazy! I can imagine that some people had a difficult time to listen to it for the first time and not being able to manage their feelings …

Pick-up #5 Moving from Emelco to Splendid recording studios, Cenizas-Uno

- TK-5110-A Cenizas

- TK-S-5110-B Uno

- Detail view

In the May 1953 issue of Discomania there is a review of Troilo’s record S-5110 Cenizas on the A side and Uno on the B side. This record is discussed as a technological turning point as the first record of the Troilo TK series to be recorded at the studios of Radio Splendid. This improved greatly the quality of their records which were known up-to-date as terrible sounding! The article says this in a very polite and diplomatic way:

“Troilo TK-S-5110

“Troilo TK-S-5110

* José Maria Rízzuti, in collaboration with Emilio Fresedo, wrote quite some pages of our tango. Today, Aníbal Troilo, with his orchestra gives us impeccably his version of Cenizas, a sentimental tribute that, as a posthumous memento, José Maria Rizzuti composed and dedicated to his girlfriend. The orchestra with its habitual seriousness, executes very well this page, that by the intention of its content and substance, deserves to be treated in the given form. On the other side, the well-known tango Uno, which not many years ago was one of the tangos that was on everyone’s lips. This work, with a melodic line, is a worthy combination with the previous side. The vocal interpretation of Jorge Casal is carefully well done, and the technical impression of both matrices has been satisfactorily performed. The tonal differentiation that is established in this recording with respect to the previous ones of the same label, is due to the fact that the recording was made in the studios of Radio Splendid, more apt for good sound than the sets at Emelco.” [Discomania ed. 11, 15.5.1953]

This Astor Piazzolla arranged version of Uno is very interesting as it doesn’t have the evenly pronouced triplet on the outro of the main refrain melody as on the first recording with Alberto Marino from 1943. The 1952 rendering is smoother and Jorge Casals voice very convincing! This could make it an interesting pick for an accessible TK tanda.

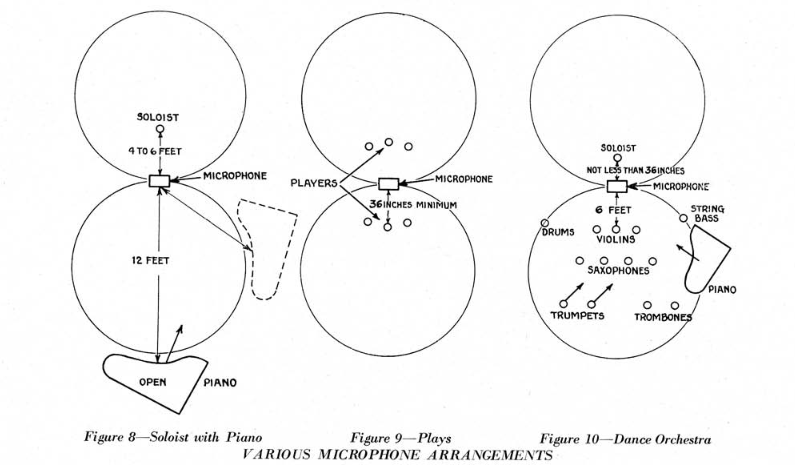

The Emelco studios and the deficient sound

The Discomania article shortly mentions in the end that the previous records of TK were recorded at the Emelco movie studios which without any doubt explains the low sound quality of the first TK recordings. When you listen to these Emelco recordings, it is as if the sound stage is quite fare away. It could have been that they had problems with arranging the microphones around the orchestra. In another edition of Discomania, I found this short news: “A new type of recording in our scene is the one performed for the Hawaiian Serenaders on the T.K. record label. It consists of making ‘set’ recordings, as if they were made in dance halls, with applause at the end of the piece. The reverberation sound system has been used in these recordings.” [Discomania, ed. 3, Dec. 1951] It is therefore plausible that this might partially been applied to the Troilo recordings or that they were experiencing with this technique.

As the Troilo orchestra does an interplay of staccato, legato and dynamic (loud and quiet) passages, the sound engineer often has to use the gain control to prevent clipping resulting in wedge-shaped effects in the waveform. In general, when listening to Troilo recordings one would wish a little bit more detail in the legato passages but often it is missing. Therefore, and taken apart that most of the later Troilo LP and CD transfers have their own problems being badly done, the Troilo recordings are in their original form as 78-rpm records slightly deficient since the beginning of the RCA Victor period. They are not optimal in the rendered detail. As if the microphones were misplaced on purpose to prevent too much dynamics. I can imagine that recording Troilo’s music was by fare one of the most demanding tasks for a sound engineer. It was without any doubt one of the most difficult orchestras to record correctly. So I guess if TK was collecting experiences, doing it with the Troilo outfit was the worst case scenario and certainly the most challenging!

Pick-up #6 Malena, Mensaje, Ivette, Un momento and La cantina

- SONDOR-2045-A 294 Malena

- SONDOR-2054-B 428 Mensaje

- TK-S-5057-A 126 Un momento

- TK-S-5286-A 723 La cantina

If the TK-S-5110 Cenizas Uno record is the qualitative pivot point of Troilo’s TK recordings, there are still quite a lot of Raúl Berón and Jorge Casal recordings which date from the sound improved period! Like for instance the very nice Berón Malena interpretation or the great recording of Mensaje or Ivette. No reason to be sad, even some from the more difficult Emelco recordings have quite acceptable sound like the beautiful vals Un momento. If you want to discover the voice of Jorge Casal try his interpretation of La cantina (well-known from the Caló-Podesta recording from the same year, 1954) and Uno.

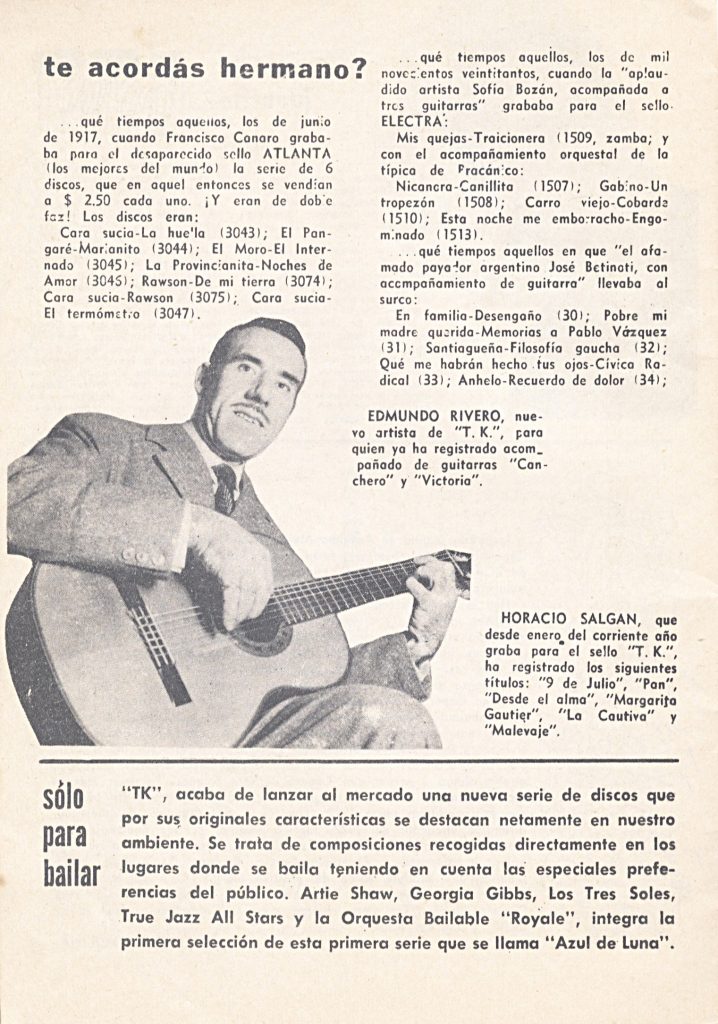

Pick-up #7 Edmundo Rivero’s guest appearance and the revival recording

For all Edmundo Rivero fans there is good news during Troilo’s six years lasting TK contract (1950-1956) there is one revival record with his emblematic singer of the late 1940s who took his retirement from the orchestra at the end of the RCA Victor period back in 1949. He comes back for one single record, TK-SB-35003, and records Sur and La ultima curda.

Edmundo Rivero who retired from the Troilo orchestra in 1949, visits Troilo for one single record at TK in 1956. They record together “La ultima curda” and “Sur”. He himself started to record as soloist under the TK label since 1954.

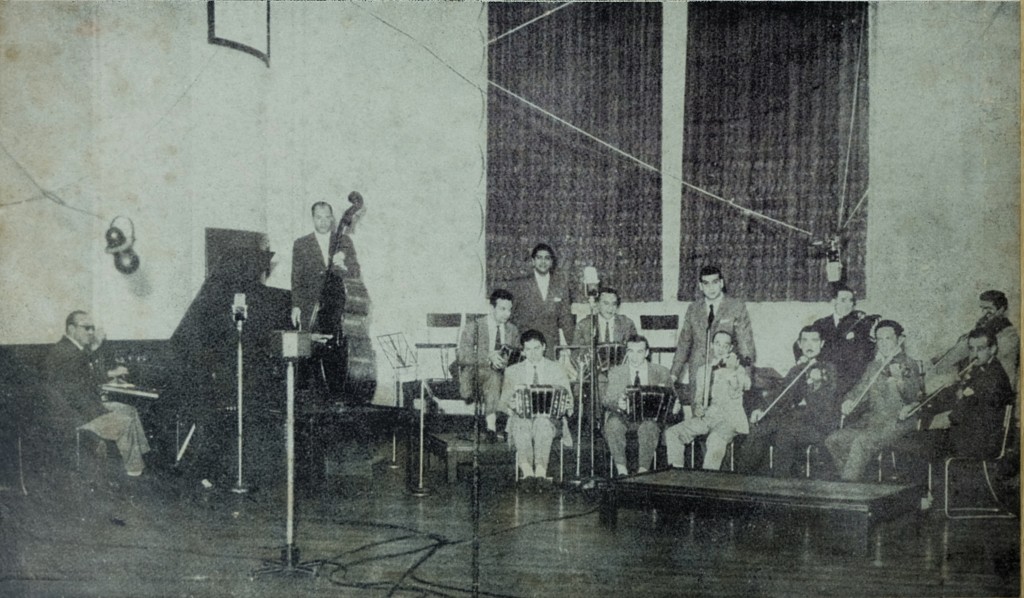

The first recordings with el polaco, Roberto Goyeneche and Ángel Cárdenas

- TK-E-10117-B Pablo

- TK-E-10136-B Milonga que pena canas

- TK-E-10136-A Vamos, vamos Zaino viejo

- TK-E-10117-A Calla

In 1956, Roberto Goyeneche and Ángel Cárdenas come to replace Raúl Berón and Jorge Casal. With Roberto Goyeneche, Troilo will record until the early 1970s! These are the very last Troilo TK recordings. With Roberto Goyeneche, Troilo records the following TK titles: Bandoneón Arrabalero, Calla, Milonga que que penas canas and Cantor de mi barrio and with Ángel Cárdenas: Quien, Chuzas, Vamos vamos Zaino viejo, Callejón and Qué risa.

In 1956, Roberto Goyeneche and Ángel Cárdenas come to replace Raúl Berón and Jorge Casal. With Roberto Goyeneche, Troilo will record until the early 1970s! These are the very last Troilo TK recordings. With Roberto Goyeneche, Troilo records the following TK titles: Bandoneón Arrabalero, Calla, Milonga que que penas canas and Cantor de mi barrio and with Ángel Cárdenas: Quien, Chuzas, Vamos vamos Zaino viejo, Callejón and Qué risa.

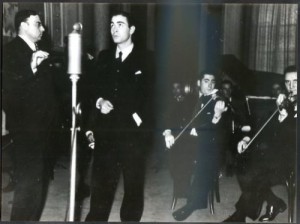

The típica Aníbal Troilo performing at the at El Club Comunicaciones with his singer Roberto Goyeneche

The TK-Sondor Uruguay connection

Like Music-Hall, TK also was interested to license its repertoire to foreign companies to increase sales on their repertoire. They quite simultaneously got a deal with Sondor in Montevideo, to issue the Troilo series in Uruguay.

- Sondor Troilo autographcard

- Back side, Sondor TK reissues

The Troilo TK records were issued from the same matrices in Uruguay but with a blue white Sondor record label and some of the A-B sides were differently recombined as compared to the original Argentine issues. The original matrix number is mentioned under the Sondor record number in smaller print.

- SONDOR-TK-2075-A 718

- SONDOR-TK-2075-B 678

- SONDOR-TK-2125 1303

- SONDOR-TK-2125 1302

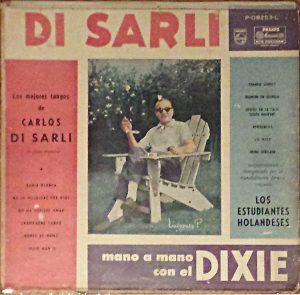

The TK Polydor Japan licence and later TK vinyls reeditions

I cannot precisely date this Japan vinyl reedition but judging from the fact that the size is still 10″ I would guess that it’s from the mid-1950s. It’s based on a deal with Polydor in Japan which allowed the Troilo-TK recordings to be issued in Japan. This series is also of perfect fidelity as compared to the original recordings!

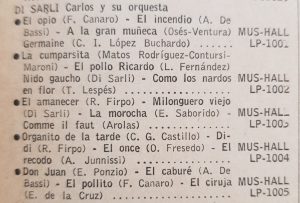

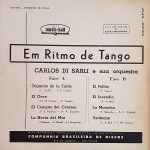

Among later vinyl reeditions are first of all TK’s own 12″ series from the early 1960s with a beautiful cover design:

The end of TK

Between 1963 and 64 the record department of Inter-Bas was transformed through a financial transaction into a new structure called Fenix S.A. which inherited the TK catalog and brand name. The remains of the company Inter-Bas became a record pressing plant. Fenix S.A. continued to release under their new record label called also Fenix mainly Jazz artists with a rather mixed success. Since the new Fenix settlement the TK repertoire became frozen and passive. The TK-discography I have seen, stops around the year 1960 with some last recordings of Alberto Castillo with the orchestra of Angel Condercuri.

Between 1963 and 64 the record department of Inter-Bas was transformed through a financial transaction into a new structure called Fenix S.A. which inherited the TK catalog and brand name. The remains of the company Inter-Bas became a record pressing plant. Fenix S.A. continued to release under their new record label called also Fenix mainly Jazz artists with a rather mixed success. Since the new Fenix settlement the TK repertoire became frozen and passive. The TK-discography I have seen, stops around the year 1960 with some last recordings of Alberto Castillo with the orchestra of Angel Condercuri.

The correct version of El Marne as recorded by Troilo on 78-rpm for TK: TK-S-5101-B 228 El Marne 1952

Some years later, 1965-66 the low budget subdivision of Music-Hall, Difusión Musical, extended its repertoire in buying the historic TK catalog from Fenix S.A. They were said to be very successful with their low priced reissues of past titles. The name and brand TK seemed to have stayed with Fenix S.A., hence they called the old TK catalog Repertorio Caravelle in order to circumvent the use of the TK brand name. “Del Repertorio Caravelle” is therefore written on all DM records dealing with TK recordings. The vinilo Troilo-Grela contains all Troilo-Grela TK recordings. On the record Ayer, Hoy y Siempre of DM there are two errant tracks which were not recorded by Troilo: La Bordona and El Marne. They seem to be later tracks recorded by the Orquesta Maffia-Gómez in 1959. This embarrassing error was passed onto the later CD Sus Mejores Momentos – Aníbal Troilo – Orfeón Records 1999!

- DM’s 90900 Series from 1981

- Back cover series 90900

The LP reissues and Eurorecord’s Archivo TK

As an overall evaluation, the TK series, even after the change to the more professional recording studio at Radio Splendid stays underneath the sound quality of the former RCA Victor recordings. In theory, the 1950s TK recordings should have been better as the state of art in sound recording technology had improved since the 1940s. But as a matter of fact the Troilo TK recordings have to be situated under the RCA Victor sound standards of the 1940s! Additionally I would like to add that the currently available CD series Archivo TK of Eurorecords makes the TK repertoire appear as to be worse as it really is, adding sometimes to the degraded impression. Their CD-transfers were not optimal and some of the tracks were initially better recorded than the CDs of the Archivo TK series present them! It’s also astonishing that the first TK vinyl reeditions are very faithful and have very good sound! Even the later DM (Difusion Musical, Repertorio Caravelle) editions which date from the late 1960s when TK repertoire got merged with Music-Hall have very fine fidelity and compare very well to the original recordings.