Since quite recently I observe a general shift in tango djing. A lot of DJs are today putting a lot of effort into recovering the most authentic sound in the milongas. This translates into investing in high end sound devices, prefering lossless sound formats over lossy codecs, analysing sound files and playing correctly tuned tracks. Trying to find tango tracks in unfiltered versions and without certain artefacts which have been added to the original recordings in later copy cycles. Unveiling somehow unplugged, purer versions of the presented repertoire with a close to perfect sound. They rather like to have some surface noise than a cleaned to death recording!

To visualise this effort, one has to be aware that the time interval which is of most concern to modern dancers, 1925-1955, the Epoca de Oro with pre and afterparty, is parallel to the technical invention of the electrical recording systems in the second part of the 1920s and ends with the introduction of the modern vinyl record and the first stereo systems around the mid-1950s when the full frequency-range recording had been finally made possible.

If we look at the records’s frequency spectrum we can see that in the beginning certain frequencies especially in the mid and high ranges weren’t yet completely present and towards the 1950s these frequencies were successively added as the recording systems improved. Let’s take the year 1926, most of the record companies licenced the new Westrex system and were able to reproduce a recording bandwidth from 50 Hertz to about 6,000 Hertz, beyond which the high frequency sensitivity declined. This had been a sensational improvement compared to the former acoustic recording systems (200 to 2,400 Hertz and sometimes less) which were in place until around 1927 mostly in an effort to empty their stock of acoustic records. None of the older acoustic recordings (nearly everything before 1927) are played in any milongas nowadays. They don’t suit our needs because they are close to inaudible and one gets easily tired from them. But listen to a very early electrical Argentinian recording, A media luz interpreted by the Orquestra Francisco Canaro from around November 1926. Though from the early electrical recording days the sound quality is astonishingly good and it still fits perfectly into a typical today’s milonga program.

- Early electrical recording: A media Luz Francisco Canaro : Instrumental Tango 1926 3:05

- And compare it to this acoustic recording just from the year before: Mesalina Francisco Canaro : Instrumental Fox-trot 1925 2:10

The missing frequencies let the tangos, we like so much, sound to our contemporary ear like if they were recorded on a different planet. And that’s maybe one of the reasons why sound engineers who transferred the early 78 rpm records to vinyl from the 1960s to the 1980s had added artefacts so that they sounded more familiar to their comtemporary hearing habits. By the late 1960s it must have been almost 15 years ago since the last 78 rpm records were sold, by the beginning of the 1980s, these old records had already disappeared from the market 30 years ago and playing 78 rpm records had been by then impossible for the large public. Therefore a new media had to be used for public reeditions to be able to still listen to the Epoca de Oro tango repertoire.

This had been in the beginning exclusively the new vinyl record and later the tape and compact cassette. A lot of people I meet are unaware of this circumstance and very much focused on the CD editions as the ultimate reference. Often they try to show me some hidden logic in how the tangos are distributed over a particular CD. Whereas the CDs often represent just a lot of 78 rpm records put together in a chronological order sometimes covering all 30 years of the larger Golden Age but in an uncomplete manner as a tango CD typically holds only around 20 to 30 tracks. This batch is often put together on an availability basis and rarely in an editorial manner. There are some exceptions though like the English Harlequin CD collection. In reality the reference is neither the CD nor the vinyl or tape. The reference is the original 78 rpm record release for mostly every published tango before 1955. A 78 rpm record looks i n size like a vinyl LP record but contains only one track per side. After 1955 started the vinyl era and some of the still present tango bands recorded then vinyl albums. In the case of D’Arienzo there were often a series of EP records and at a later stage a LP regrouping the EP releases. Di Sarli’s last recordings with Philips were later published on a single LP. I have a 1980’s reedition of this stereo record.

n size like a vinyl LP record but contains only one track per side. After 1955 started the vinyl era and some of the still present tango bands recorded then vinyl albums. In the case of D’Arienzo there were often a series of EP records and at a later stage a LP regrouping the EP releases. Di Sarli’s last recordings with Philips were later published on a single LP. I have a 1980’s reedition of this stereo record.

A typical artefact which had been introduced back then to the original recordings, is called a reverberation effect. While listening through the same titles of my collection I can distinguish versions with and without an echo effect. Famous examples are some of the early D’Arienzo recordings with Rodolfo Biagi on the piano. The initial recordings date from 1935 to 1939. If you listen to the echo containing versions, you have the impression that the orchestra must have been quite huge, recorded in a big hall with a lot of musicians. Whereas the standard version without the echo effect, sounds like very close and intimate. If I compare it to classical music, the echo version is the symphonic orchestra and the version without echo the chamber music.

The first known delay effects where available since around the 1950’s and were called Tape echo. To be more precise the echo effect is called a delay effect. With reverberation there are multiple delays and feedback so that individual echoes are blurred together, recreating the sound of an acoustic space. And I think this was precisely the intention of the sound engineers when they later added the echo to the old recordings: To add more depth to the flat sounding recording of the mono era. With the upcoming stereo culture of the 1960’s and 1970’s they wanted to give these old records a face lift and make them enter into the stereo age. As a side effect the echo also camouflaged imperfections of the original sound recording. And indeed when you listen to the echoed versions there is nearly no surface noise left. They make a clean impression.

Let’s have a closer look to the edition history of some of these tangos.

El cencerro performed by Juan D’Arienzo in 1937 is in it’s original 78 rpm record version of course without any echo effect. Later the same label, RCA Víctor, reissued El cencerro on a LP sampler called Evocando el Ayer, Vol.4, Serie Apoyando el Buen Tango CAL-3234.  The 6 D’Arienzo instrumental LPs of this collection are very accurate reproductions of the original 78 rpm releases. They just contain some dating errors and some have no date indications at all but the sound quality is outstanding with no to very few reverberation effects and close to perfect tuning. This series had been issued somewhere in the mid to late 1970’s. In 1980 El cencerro had been again republished by RCA Víctor, this time on a 10 LP set called Serie Tango De Ayer, Vol. 3 D’Arienzo Biagi, containing a strong echo effect. It’s interesting to see how this tango is transfered later to CD: The El Bandoneón CD edition El Rey Del Compás EBCD43 (1999) as well as the Serie Tango Argentino CD Juan D’Arienzo Sus Primeros Exitós Vol. 2 (around 2004), seem to be based on the 1980 echo remix by RCA Víctor. Also Milonga del corazón is the same version on the newer RCA Víctor BMG CD El Rey Del Compás 70 años El

The 6 D’Arienzo instrumental LPs of this collection are very accurate reproductions of the original 78 rpm releases. They just contain some dating errors and some have no date indications at all but the sound quality is outstanding with no to very few reverberation effects and close to perfect tuning. This series had been issued somewhere in the mid to late 1970’s. In 1980 El cencerro had been again republished by RCA Víctor, this time on a 10 LP set called Serie Tango De Ayer, Vol. 3 D’Arienzo Biagi, containing a strong echo effect. It’s interesting to see how this tango is transfered later to CD: The El Bandoneón CD edition El Rey Del Compás EBCD43 (1999) as well as the Serie Tango Argentino CD Juan D’Arienzo Sus Primeros Exitós Vol. 2 (around 2004), seem to be based on the 1980 echo remix by RCA Víctor. Also Milonga del corazón is the same version on the newer RCA Víctor BMG CD El Rey Del Compás 70 años El

Esquinazo 1937-1938. It looks very much as if this LP had been the initial matrix for all follow-up D’Arienzo echo containing transfers. Therefore most of the dancers in America and also in Europe know only (or at least only had access to) the echo version as you can see on nearly all Youtube dancing videos like this memorable performance by

Esquinazo 1937-1938. It looks very much as if this LP had been the initial matrix for all follow-up D’Arienzo echo containing transfers. Therefore most of the dancers in America and also in Europe know only (or at least only had access to) the echo version as you can see on nearly all Youtube dancing videos like this memorable performance by

[youtube]http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=6f_BYsvVUz4[/youtube]

Please see also in this context the mystery about the Don Esteban recording as described on Johan’s website and which appears to be the only ever reedition of this tango by RCA Víctor. According to Johan it looks like the masters might have been lost. This is particularily sad as this reedition and all others have this strong echo effect and the El Bandoneón and RCA BMG CD copies inherrited it! Also this version of Don Esteban appears to be slightly different to the japanese CTA version which would suggest that there might have been two seperate recording sessions back in the 1930’s …

See here the sound samples:

- Don Esteban Juan D’Arienzo 1936 3:25 (with echo) From the LP Serie Tango De Ayer, Vol. 3 D’Arienzo Biagi

- El cencerrro Juan D’Arienzo 1937 2:41 (with echo) From the LP Serie Tango De Ayer, Vol. 3 D’Arienzo Biagi

- El cencerrro Juan D’Arienzo 1937 2:42 (without echo) 1:00 Extract of the Audio Park CD version

In a way the echoed version of El cencerro made it into the salón and became some kind of accepted sound icon.

Maybe as a tribute to Juan D’Arienzo as he only made one recording of this particular tango back in 1937 when the recording techniques were still evolving. The echo version could be seen as an attempt to port the thin 1937 recording to a more space filling version as represented by the late D’Arienzo repertoire.

On the other hand nothing prevented the King of the Beat to publish a monumental version of El cencerro during his lifetime recording sessions which covered still another 20 years during the full frequency range stereo era from 1955 to 1975 — but as a matter of fact he didn’t, maybe he just forgot to do so … 🙂

If you want a version without the delay remix, you need to get Audio Park’s Epoca De Oro Vol. 1 APCD 6501 or CTA’s Juan D’Arienzo Vol.3 CTA-303. The japanese editions are based on their own 78 rpm transfers.

Now with this particular case presented in detail, I don’t know in how far people are aware that the echoed version is a pure invention? From the strict point of view of authenticity the echo version is untrue, some would say a lie. Back in the end of the 1970’s it had another meaning as we have seen and just until a couple of years ago it had been the only available version of this tango on second generation media, LPs, CCs and CDs! A lot of music in that time used extensively delay effects. Like on the 1977 David Bowie album Low which is interestingly from the same record label as the Juan D’Arienzo recordings, RCA Victor. This suggests that there must have been an interventionalist sound engineer at this company who added all sorts of artefacts to the historic recordings: Echo, tempo acceleration, low pass filters, etc. As to update these tunes to the taste of the day. And indeed other lables have been much more fidel when they restored and reedited their historic tango repertoire. In comparison EMI who inherited the ODEON catalogue had issued mostly very correct and authentic sounding LPs …

[youtube]Ihttp://www.youtube.com/watch?v=mkNmilE9ibk[/youtube]

Another added artefact to the original recordings is incorrect tempo as I just mentioned. This is actually by far a wider spread problem than echo effects, too strong noice reduction, wrong preamplification schemes or other record problems. The incorrect pitch which arises from incorrect record transcript sessions is the kind of problem which remains often unnoticed, but seems to haunt the listener unconsciously. Let’s see an example: Age Akkerman has described recently on his blog a case of an out of tune recording, Di Sarli’s interpretation of El ciruja. He explains that he didn’t like this tango before and how retuning the tango to the correct pitch changed his mind and appreciation of this tango. Different tonal tunings can create different feelings or emotions in the listener. This can lead in the worst case to refuse and unlike a track. Most of these tonal shifts are due to a too fast running turntable during the transfer session. If you speed up or slow down a turntable you will hear how the keys of the music move around and change. Nobody really knows how these sometimes quite huge differences made it into the transfer recordings, it could have been via damaged transfer turntables or on “an early reel-to-reel tape recorder by changing the diameter of the capstan drive shaft, or using a different motor” [Wikipedia]. Nor do we really know if these changes had been done intentionally or by accident. But it seems that a lot of tangos are affected. Here is a quick test you can do in your own music collection to find such pitch problems: select the same tango, same recording date but from different sources/CD editions and check the duration and BPM fields. Are they different?

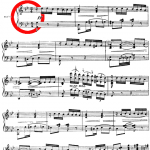

A couple of days ago I have recognised that there is something wrong with the pitch of Carlos Di Sarli’s Cosas olvidadas which sounded just too fast. Through an analysis of the partition , determinating the original key most proberly used by the band in their arrangement and carefully listening to the voice in the recording, while slowing down the track, I have pitched down the track by a total factor of around 2.5%. Now it sounds natural. For a comprehensive guide to retuning tracks, please see Age Akkerman’s paper Lost in Keys and check the examples on his website. This kind of pitch shift can get really dangerous when women voices are involved. They are already very high and if they are then pitched up further they arrive in regions where they can produce a pain in the ear (See my article on Too fast El Bandoneón recordings).

, determinating the original key most proberly used by the band in their arrangement and carefully listening to the voice in the recording, while slowing down the track, I have pitched down the track by a total factor of around 2.5%. Now it sounds natural. For a comprehensive guide to retuning tracks, please see Age Akkerman’s paper Lost in Keys and check the examples on his website. This kind of pitch shift can get really dangerous when women voices are involved. They are already very high and if they are then pitched up further they arrive in regions where they can produce a pain in the ear (See my article on Too fast El Bandoneón recordings).

See here the different version of Cosas olvidadas as selected from my music collection for a comparison:

Cosas olvidadas Carlos Di Sarli : Roberto Rufino TA Canta Roberto Rufino Sus Primeros Exitos Vol. 1 Duration 2:19

Cosas olvidadas Carlos Di Sarli : Roberto Rufino RR Various Artists 1941-1956 Vol. 3 Duration 2:15

Cosas olvidadas Carlos Di Sarli : Roberto Rufino BATC-DIEGON Milonga Del Sentimiento Duration 2:21

Cosas olvidadas Carlos Di Sarli : Roberto Rufino El Bandoneón El Señor Del Tango Duration 2:17

Cosas olvidadas Carlos Di Sarli : Roberto Rufino Retuned version from Sus Primeros Exitos Vol. 1 Duration 2:23

Now one could say that these different speeds don’t have any effect on the audience but I have talked to some dancers and it seems that often these pitch shifts are noticed, in most of the cases unconsciously, they say then, the music is not so nice or restless. With some DJ collegues I also recognised that they won’t play repertoire of which they have a lot of too fast transfers. they say then: “Ah, Donato, I don’t like” or “Late D’Arienzo is too hysterical”. Other DJs like these faster versions if they need to mobilise energy in tired dancers, then again I think it would be an advantage to first correct the tunings and to operate in a second step a further up pitching while locking the keys, this can be done live with modern dj programs like Mixxx or Traktor. That way tangos can be speed up without affecting the tonal keys.

- Quintessentially find here a in D retuned version of El cencerro by Age Akkerman based on a track taken from the Remy Kooij collection (version with a light echo).